Inflation targeting means Central Banks are responsible for using monetary policy to keep inflation close to the agreed target (usually around 2%).

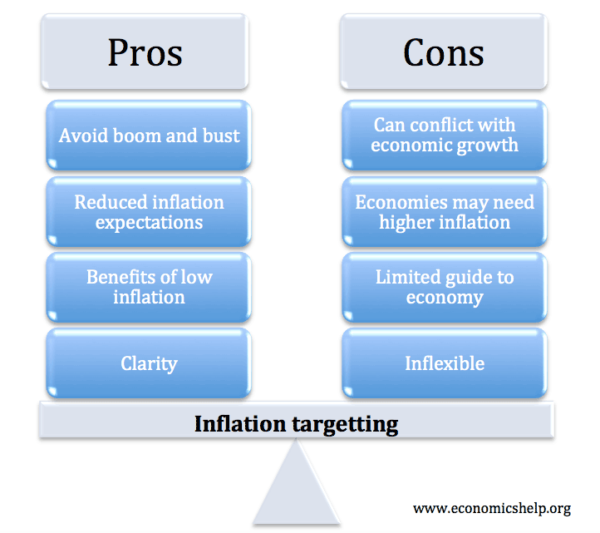

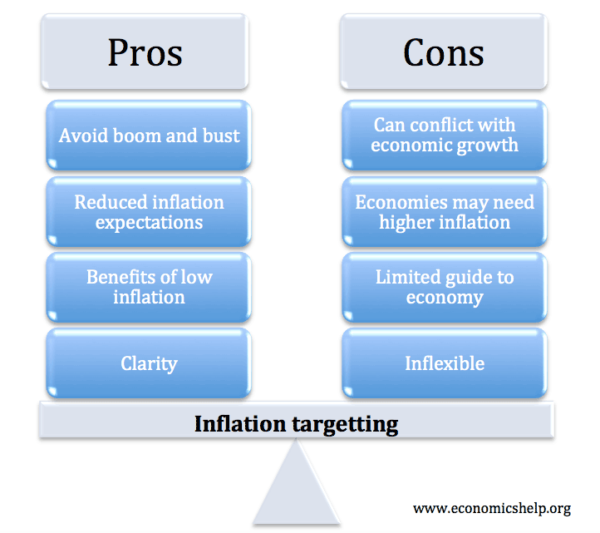

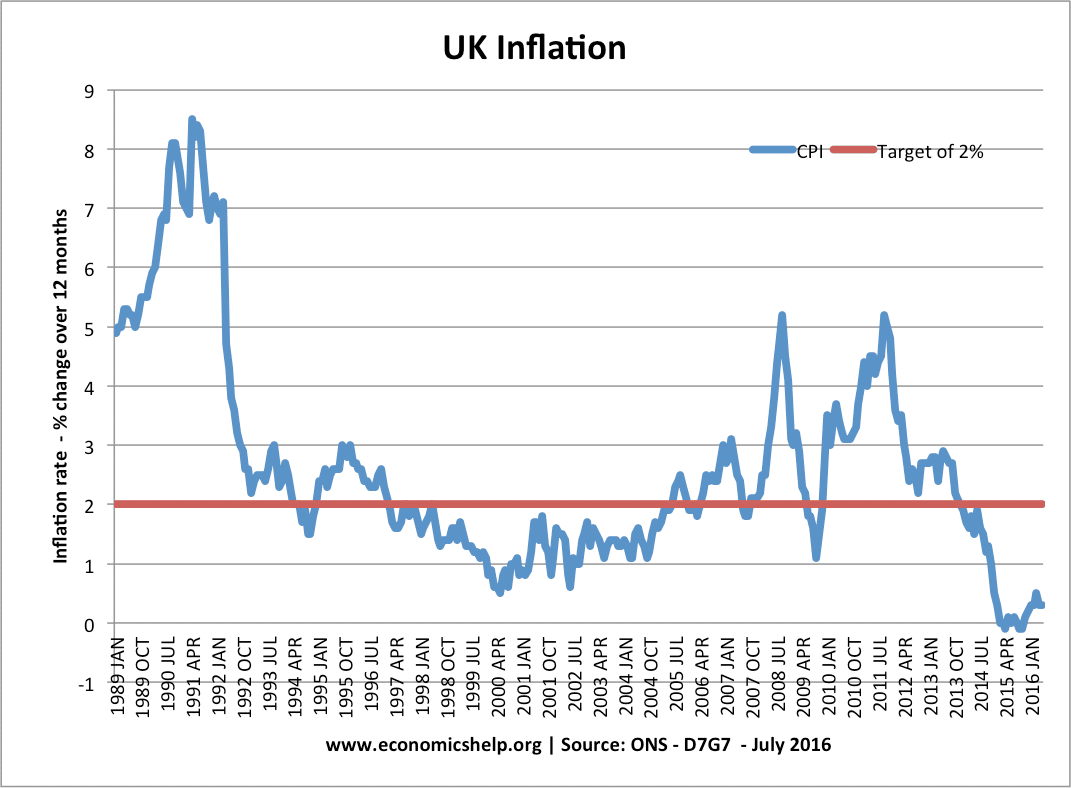

Since the mid-1990s, inflation targeting has become widely adopted by developed economies, such as UK, US, and the Eurozone. Inflation targets were introduced to help reduce inflation expectations and help avoid the periods of high inflation which destabilised economies in the 1970s and 80s. However, since the recession of 2008, economists have begun to question the importance attached to inflation targets and are worried that a strict commitment to low inflation can conflict with other more important macroeconomic objectives.

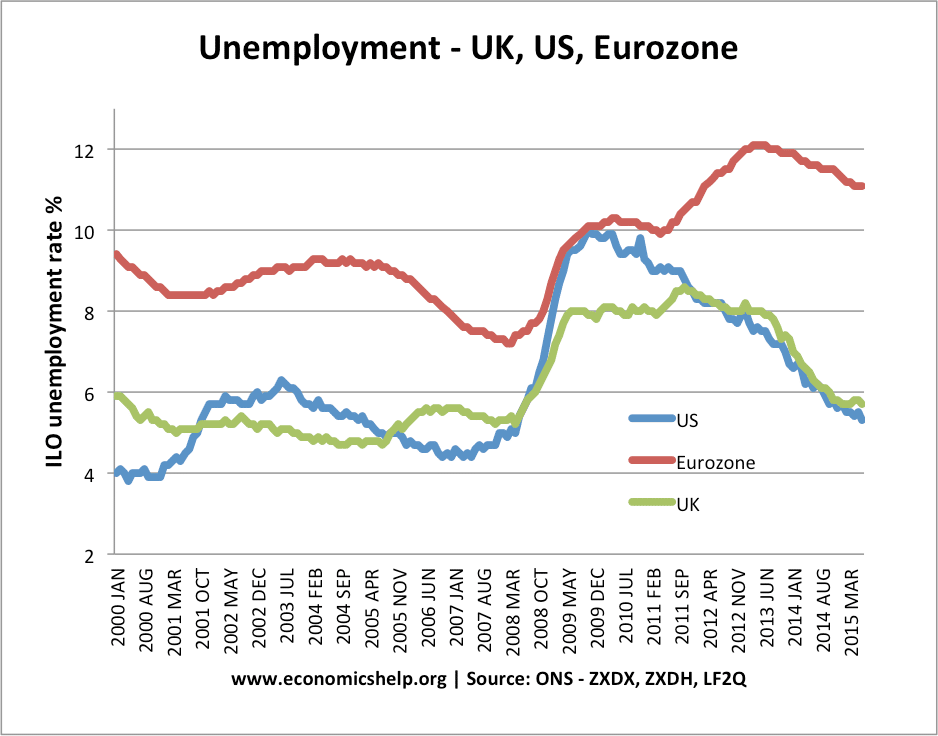

2. Central Banks start to ignore more pressing problems. The ECB set monetary policy to keep inflation in the Eurozone on target. Yet, by targetting inflation, they appeared to be downplaying the costs of rising unemployment. In 2011/12, the ECB seemed remarkably unconcerned about the Eurozone’s slide into a double-dip recession. Rather than trying to prevent a prolonged slump, they were fixated on the importance of low inflation.

Inflation above target can impose costs on the economy such as uncertainty, loss of competitiveness and menu costs, but arguably these costs are much less significant than the social and economic costs of mass unemployment. Unemployment in Spain reached 25%, but there was little monetary stimulus in the Eurozone because the ECB is worried about inflation at 2.6% – This is giving low inflation too much priority in times of a recession.

3. Sometimes you need a higher inflation rate. This point is controversial, but in a liquidity trap, some economists, such as Paul Krugman argue that it can be necessary to target a higher inflation rate – to help overcome deflationary pressures.

For example, in 2012, Germany had a current account surplus of 6%. Yet, Southern European countries had a large current account deficit and lack of competitiveness. To restore competitiveness, Southern European countries are pursuing deflationary policies which are risking recession and deflation. If Germany had higher consumer spending and higher inflation, then this would make the readjustment process in the Eurozone less painful.

4. Inflation targets are limited.

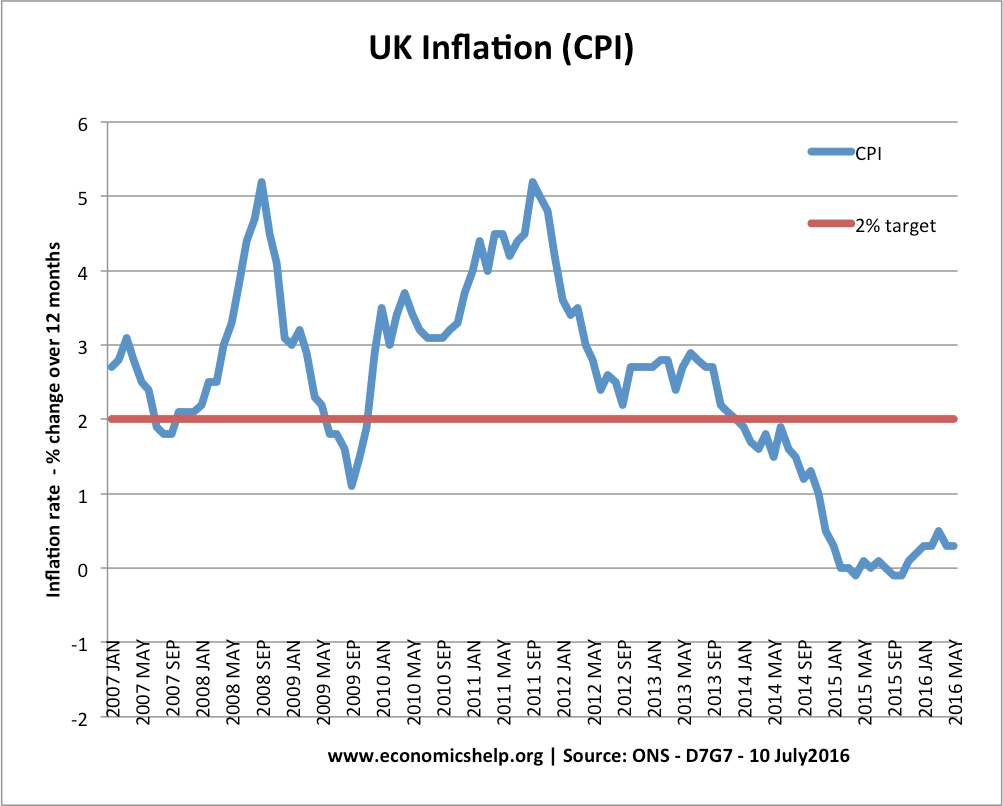

Inflation targetting successful in keeping inflation low. The low inflation in the early 2000s – suggested a balanced economy – but there was a credit bubble, housing bubble and rise in consumer spending.

After the 1992 recession, the UK had a long period of economic expansion and low inflation. This suggested inflation targeting was very successful in avoiding inflationary booms. To some extent this was true. However, the low inflation disguised an asset and banking boom and bust. This isn’t so much a criticism of inflation targeting, but it is a clear limitation. Low inflation doesn’t mean the economy has an underlying stability.

5. A large output gap doesn’t necessarily lead to deflation.

An IMF paper shows that countries with a large negative output gap often don’t see a fall in inflation. Therefore, targeting inflation alone can lead to a suboptimal response. (Dual mandate at Fed)

6. Which inflation measure to use? There can be significant differences between RPI and CPI. Also, even CPI can be greater than underlying inflation which excludes volatile prices, such as energy and food. See: Different measures of inflation

Inflation targets can have various benefits, especially during ‘normal’ economic circumstances. However, the prolonged recession since the credit crunch of 2008 has severely tested the usefulness of inflation targets. There is a danger that Central Banks give too much weighting to low inflation when there are a much more serious economic and social problems such as unemployment.

One solution would be to give an equal weighting to an inflation target and output gap target. The UK and US do actually have this dual target, though the inflation target often seems to be given the highest importance – because it has the greatest visibility.

My bigger criticism rests with the ECB (which has only a single mandate for low inflation). In the past, they have given the impression of under-estimating the economic cost of prolonged unemployment and a persistent output gap in the Eurozone. Furthermore, given the structural problems of the Eurozone, it is even more important to have flexibility in the inflation target within the Eurozone.

The ECB argued that if they change their inflation target, they will lose credibility. But, this indicates they feel inflation is the main criteria for judging monetary policy. There also needs to be credibility in reducing unemployment and promoting economic growth.

I have nothing against inflation targets if the Central Bank gives as much importance to the dual target of unemployment/output gap. Also in exceptional times – liquidity trap/recession – there needs to be more flexibility on inflation – and a willingness to tolerate higher inflation, where necessary. In certain circumstances – it may even be necessary to increase the inflation target.

Related